Quantum Mechanics Part II: Dynamics & Continuous States

Dynamics

The Time Evolution Operator

Dynamics for vectors, including those in Hilbert space, can generically be modeled as

\[\ket{\Psi(t_2)}=\mathbf{U}(t_2,t_1) \ket{\Psi(t_1)}\]where \(\mathbf{U}\) is a “time evolution operator” that maps states from one time to another. Usually we set \(t_1=0\) and \(t_2=t\) and simply write \(\mathbf{U}(t,0) \rightarrow \mathbf{U}(t)\).

At this point \(\mathbf{U}\) could be anything, but there’s one thing we want \(\mathbf{U}\) to do, and that’s conserve inner products. Susskind calls this “conservation of information” and it implies that for arbitrary \(t\) it’s true that \(\bk{\Psi(t)}{\Phi(t)} = \bk{\Psi(0)}{\Phi(0)}\) or

\[\bra{\Psi(0)}\mathbf{U}(t)^{\dagger}\mathbf{U}(t)\ket{\Phi(0)} = \bk{\Psi(0)}{\Phi(0)}\]So \(\mathbf{U}^{\dagger}\mathbf{U} = I\) and therefore \(\mathbf{U}\) is unitary. A corollary to this is that the magnitude of state vectors is conserved over time.

These results are for finite evolutions. What about infinitesimal ones? In the limit, the linear infinitesimal approximation of \(\mathbf{U}\) is

\[\mathbf{U}(\epsilon) = I - \epsilon i \mathbf{H}\]Where \(\epsilon\) is a very small time interval, \(\mathbf{H}\) is a constant operator, and \(-i\) is factored in so that the predictions of this model match experimental measurements. What does this operator do to \(\ket{\Psi}\)?

\[\begin{align*} \ket{\Psi(\epsilon)} &= \mathbf{U}(\epsilon) \ket{\Psi(0)} \\ \ket{\Psi(\epsilon)} &= (I - \epsilon i \mathbf{H}) \ket{\Psi(0)} \\ \frac{\ket{\Psi(\epsilon)} - \ket{\Psi(0)}}{\epsilon} &= -i\mathbf{H} \ket{\Psi(0)} \\ \end{align*}\]As \(\epsilon \rightarrow 0\),

\[i \hbar \frac{\partial \ket{\Psi}}{\partial t} = \mathbf{H}\ket{\Psi}\]where \(\hbar\) is factored in to make units work, it’s value is about \(10^{-34} kg \space m^2/s\). This PDE is called the generalized Schrodinger equation.

Before moving on to solve the GSE, we can learn a bit about \(\mathbf{H}\) by asking what, if anything, the unitary condition on \(\mathbf{U}\) implies about it:

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{U}(\epsilon)^\dagger \mathbf{U}(\epsilon) &= (I - \epsilon i \mathbf{H})^\dagger (I - \epsilon i \mathbf{H}) \\ &= (I + \epsilon i \mathbf{H}^\dagger) (I - \epsilon i \mathbf{H}) \\ &= I - \epsilon i \mathbf{H} + \epsilon i \mathbf{H}^\dagger = I \\ \end{align*}\]So \(\mathbf{U}\) being unitary implies \(\mathbf{H}\) is Hermitian and therefore can represents an observable, which, as we’ll see, is the quantum Hamiltonian.

In CM recall that Hamiltonians represent the total energy of a system and relate to the system’s dynamics through the Poisson bracket:

\[\dot{L}=\{L,H\}\]\(L\) here is any quantity defined over phase space \(L(q,p)\). Using the GSE it’s straightforward to show that a similar relation exists in QM but for expected values:

\[i \hbar \frac{d}{dt}\left<\mathbf{L}\right> = \left<\left[\mathbf{L},\mathbf{H}\right]\right>\]\(\left[\mathbf{L},\mathbf{H}\right] = \mathbf{L}\mathbf{H} - \mathbf{H}\mathbf{L}\) is called the commutator. From it we see that if a quantity commutes with \(\mathbf{H}\) then it’s conserved (in expectation), and more generally any function of a quantity that commutes with \(\mathbf{H}\) is conserved (in expectation). This is like in CM where if the PB is \(0\) then \(L\) is conserved.

Note that in QM expected values don’t change due to the measurables changing. Those are fixed for a given operator (for example \(\pm 1\) for spin). Instead, expected values change because the measureables’ associated probabilities change, and to calculate how they change we have to solve the generalized Schrodinger equation.

Solving the Generalized Schrodinger Equation

Solving the GSE is easiest in the energy basis where \(\mathbf{H}\) is diagonal and an arbitrary state vector can be written as

\[\ket{\Psi(t)} = \sum_i a_i(t) \ket{E_i}\]\(\ket{E_i}\) is an energy eigenvector satisfying \(\mathbf{H}\ket{E_i} = E_i\ket{E_i}\). Inserting this into the GSE gives

\[\begin{align*} \sum_i \dot{a}_i(t) \ket{E_i} &= -\frac{i}{\hbar} \mathbf{H} \sum_i a_i(t) \ket{E_i} \\ &= -\frac{i}{\hbar} \sum_i E_i a_i(t) \ket{E_i}\\ \end{align*}\]This is a simple first-order ODE for each component. The solution is

\[a_i(t) = a_i(0) e^{-iE_it/\hbar}\]Compared to the general form of an oscillator \(\exp(-i \omega t)\) we see that \(E/\hbar\) plays the role of frequency in QM.

This solution assumes we’re working in the energy basis. What if we’re given a state vector in a different basis and want to compute dynamics? Given a general state vector \(\ket{\Psi}\) in a non-energy basis (such as the spin basis \(\ket{+z}\), \(\ket{-z}\)), factor the Hamiltonian according to \(\mathbf{H} = \mathbf{P}\mathbf{\Lambda}\mathbf{P}^{\dagger}\), then the state in the energy basis is \(\mathbf{P}^{\dagger}\ket{\Psi}\). In terms of components \(a_i = \bk{E_i}{\Psi}\), where \(a_i\) is the \(i\)th component of \(\ket{\Psi}\) in the energy basis. This is all summarized by the general solution to the SE:

\[\ket{\Psi(t)} = \sum_i \bk{E_i}{\Psi(0)} e^{-iE_it/\hbar} \ket{E_i}\]Continuous States

Making the Transition

So far we’ve looked at what I’m going to call discrete states—discrete in the sense that eigenvalues are countable and states are written as a finite sum over basis vectors. But we’d also like to model continuous quantities, like position and momentum. How are continuous states modeled?

The answer is that they’re modeled in the same way as discrete states: by the principles of QM. The trick is to keep in mind that the principles don’t require states to be discrete—they only require them to be vectors, and vectors can be anything, discrete or continuous, as long as they satisfy the mathematical axioms of vectors (they commute, have an inverse, etc). Complex functions in this sense are continuous vectors and they’re exactly what are used to model continuous states.

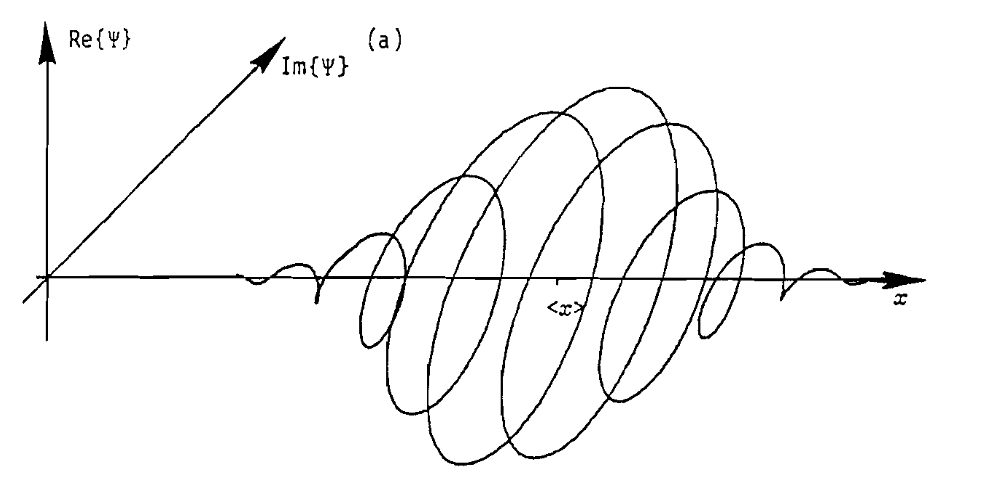

Wave Functions

In terms of notation, a continuous state is associated with a wave function \(\psi(x)\) which takes a complex input and returns a complex output. Wave functions are defined with respect to a basis just as discrete vectors are, and their values can change from one basis to another, just as discrete vectors can. The bra-ket notation is useful for wave-functions like it is for discrete vectors. The discrete representation

\[\ket{A} = \sum_i a_i \ket{i}\]becomes

\[\ket{\Psi} = \int \psi(x) \ket{x} \,dx\]where \(x\) labels eigenvalues and \(\ket{x}\) is the associated eigenvector. In the analogy with discrete states, \(\psi(x)\) is like a continuous set of coefficients \(a_i\). Another way to think of wave functions is in terms of a state vector’s projection onto a basis. For example, in the \(x\) basis the wave function is

\[\psi(x) = \bk{x}{\Psi}\]The probability of measuring a continuous eigenvalue \(x\) is analogous to the discrete case—it’s \(\psi^*(x)\psi(x)\), which can be interpereted as a probability density function for the random variable \(x\). Keep in mind though that this is a probability density and therefore we technically shouldn’t say things like “the probability of measuring \(x\)” because the probability of a single value on a pdf is \(0\). Instead, we should talk about the probability of measuring \(x\,dx\), which is the value of \(x\) around some small region \(dx\), this gives a non-zero number for the probability.

Continuous Operators

Operators on continuous vectors are similar to operators on discrete vectors: they’re linear and Hermitian. To verify linearity you check that they distribute over the sum of functions with constants factoring out. In other words, \(\mathbf{L}(a\psi(x)+b\phi(x)) = a\mathbf{L}\psi(x) + b\mathbf{L}\phi(x)\)

Examples of linear operators include multiplication by \(x\) and differentiation by \(d/dx\).

Hermiticity is a bit trickier to verify. It occurs when

\[\bke{\psi}{\mathbf{L}}{\phi} = \bke{\phi}{\mathbf{L}}{\psi}^{*}\]Where

\[\bke{\psi}{\mathbf{L}}{\phi} = \int \psi^*(x)\mathbf{L} \phi(x) \,dx\]For example, if \(\mathbf{L}=x\) this is

\[\begin{align*} \bke{\psi}{x}{\phi} &= \int \psi^*(x) x \phi(x) \,dx \\ &= \left( \int \psi(x) x \phi^*(x) \,dx \right)^* \\ &= \bke{\phi}{x}{\psi}^* \end{align*}\]Therefore the operator \(x\) is Hermitian. Note that the \(\dagger\) from discrete operators gets replaced by \(*\) for functions because there are no transposes for functions. Applying the same test to \(d/dx\) we find that it’s not Hermitian, but if we multiply it by \(i\) it is.

Position & Momentum

How are eigenvalues and eigenvectors computed for continuous operators? For position the operator is \(x\) and its eigenvalues are denoted by \(x_0\). The eigenequation is

\[x\psi(x) = x_0 \psi(x)\]or

\[(x-x_0)\psi(x) = 0\]If \(x \ne x_0\) then this requires \(\psi(x) = 0\), and when \(x = x_0\) then \(\psi(x)\) can be anything, but because \(\psi\) is a probability amplitude, it must integrate to \(1\), so the eigenfunction is

\[\psi(x) = \delta(x-x_0)\]This states the obvious fact that if a particle is measured at \(x_0\) then it’s only at \(x_0\). It’s important to note that \(\delta\) is not a function, it’s a distribution, and as such belongs inside an integral:

\[\begin{align*} \ket{\Psi} &= \int \psi(x) \ket{x} \,dx \\ &= \int \delta(x-x_0) \ket{x} dx \\ &= \ket{x_0} \end{align*}\]It’s also important to note that this delta-function model of position is a mathematical idealization. If wavefunctions did in-fact collapse to delta-functions when position was measured, the uncertainty in position would be zero and, because of the position-momentum uncertainty relation, this would force momentum uncertainty be infinity, which isn’t physically meaningful.

What are the eigenfunctions of momentum? For momentum the set-up and solution are the same, but now \(\bar\psi\) is used to denote a wave function in momentum space:

\[p\bar\psi(p) = p_0\bar\psi(p) \\ \rightarrow \bar\psi(p) = \delta(p-p_0)\]The \(\delta\) function solution here and for position are not especially insightful, but when we look at momentum in the \(x\) basis things are more interesting. In the \(x\) basis, from experimental insight, the momentum operator changes from \(p\) to \(-i\hbar \, d/dx\). The eigenequation becomes

\[-i\hbar \frac{d}{dx}\psi(x) = p \psi(x)\]and the solution is

\[\psi(x) = Ae^{ipx/\hbar}\]Note that because this is a wavefunction in the \(x\)-basis it’s considered a function of \(x\) and not \(p\). The \(p\) appears because each value of momentum has a different wavefunction associated with it, so \(p\) acts more like a parameter or index.

The constant \(A\) is determined by normalization:

\[\bk{\psi}{\psi} = \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \psi(x)^*\psi(x) \,dx = 1\]But this gives

\[|A|^2\int_{-\infty}^{\infty} \,dx = 1\]Which is undefined. This reflects the fact that when particles are unconstrained in space the planewave solution \(\exp(ipx/\hbar)\) is physically unrealistic. In practice, particles are either constrained in space such that the integration limits are finite, or, if they are un-constrained in space, they’re acted on by a potential such that the wave-function goes to zero sufficiently quickly for the integral to converge.

Changing Basis

Generally speaking, a state vector \(\ket{\Psi}\) can be represented in any basis. For example, in the \(x\) basis \(\psi(x) = \bk{x}{\Psi}\), in the momentum basis \(\bar\psi(p) = \bk{p}{\Psi}\), etc. Because these representations ultimately correspond to the same state, namely \(\ket{\Psi}\), there must be a way to transform between them. How do we transform between the \(x\) and \(p\) basis?

The trick is to use the identity operator:

\[I = \int \ket{x}\bra{x} \cdot \,dx\]Where “\(\cdot\)” is a placeholder for the vector which the operator acts on. Inserting this into the momentum-representation gives

\[\begin{align*} \bar\psi(p) &= \bk{p}{\Psi} \\ &= \bke{p}{I}{\Psi} \\ &= \int \bk{p}{x}\bk{x}{\Psi}\,dx \\ \end{align*}\]But

\[\begin{align*} \bk{p}{x} &= \int A e^{-ipx'/\hbar} \delta(x'-x) \,dx' \\ &= Ae^{-ipx/\hbar} \end{align*}\]And \(\bk{x}{\Psi} = \psi(x)\), so

\[\bar\psi(p) = A\int e^{-ipx/\hbar} \psi(x) \, dx\]Which is the formula for converting a position-space wave function into its momentum-space complement. The derivation of the inverse operation is similar. The result is

\[\psi(x) = A \int e^{ipx/\hbar} \bar\psi(p) \,dp\]So position and momentum space are related by the Fourier transform. This leads to the interpretation that momentum space is the spatial frequency domain of position space, where spatial frequency is given by \(k=p/\hbar\).

How do operators change basis? Operators change basis like matrices do: \(\mathbf{L' = \mathbf{U} \mathbf{L} \mathbf{U}^{-1}}\), where \(\mathbf{L}\) is the operator of interest, \(\mathbf{L}'\) is the transformed operator, and \(\mathbf{U}\) is a unitary change-of-basis operator. Because \(\mathbf{U}\) is unitary and we’re working with continuous operators we can set \(\mathbf{U}^{-1} = \mathbf{U}^*\).

How does this work for position and momentum? The relevant change-of-basis operator is the Fourier transform \(\mathbf{F}\). Is it unitary? Yes, because \(\mathbf{F}^*\mathbf{F}\psi(x) = \psi(x)\), which implies that \(\mathbf{F}^*\mathbf{F}=I\). Let’s use \(\mathbf{F}\) to derive the position operator in momentum space, call it \(\mathbf{\bar X}\).

\[\begin{align*} \mathbf{\bar X} \bar\psi(p) &= \mathbf{F}\mathbf{X}\mathbf{F}^* \bar \psi(p) \\ &= \mathbf{F} \mathbf{X} \psi(x) \\ &= \mathbf{F} x \psi(x) \\ &= i\hbar \frac{d}{dp} \bar \psi(p) \end{align*}\]Where the last step comes from a Fourier transform identity. So the position operator in momentum-space has a similar form to the momentum operator in position space, namely \(i\hbar d/dp\).

Another way to determine or verify an operator in a new basis is through the use of commutators. The reason is that commutators are basis independent. For example, \([\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{P}] = [\mathbf{\bar X}, \mathbf{\bar P}] = i\hbar\). This method may require some guessing and checking, whereas the unitary method above is an explicit calculation that should always give the correct result, though it may be more challenging to acquire mathematically.

As a practical note, when working with operators it’s helpful to supply them with a test function to act on, otherwise it isn’t always clear exactly how they simplify.

Uncertainty

Going back to the discussion of commutators, we found that two observables are simultaneously knowable iff their operators commute. Do the operators for \(x\) and \(p\) commute? The answer is no. Given \(\mathbf{X}=x\) and \(\mathbf{P}=-i\hbar d/dx\) the commutator is

\[[\mathbf{X}, \mathbf{P}] = i\hbar\]Which means position and momentum aren’t simultaneously knowable—measuring one destroys information about the other, and vice versa. They are said to be incompatible. Just how incompatible? Defining incompatibility in terms of the standard deviation \(\sigma\) of an operator we find from the general uncertainty principle that

\[\sigma_x \sigma_p \ge \frac{\hbar}{2}\]The lower limit on simultaneous uncertainty is reached when either \(\psi\) or \(\bar \psi\) are Gaussian function.

What happened to y and z? For the sake of simplicity I’ve focused on measurements taken in one dimension, namely \(x\), but generalizing to \(y\) and \(z\) is straighforward. The position operator for \(y\) is \(y\) and the momentum operator for \(y\) is \(-i\hbar\, \partial/\partial y\). And similar applies to \(z\). Just note that the derivatives change from totals to partials, and the momentum operator as a whole becomes \(-i\hbar \nabla\).

Are measurements compatible across dimensions? The answer is yes. Using \(i\) and \(j\) to index spatial dimensions we get

\[\begin{align*} [\mathbf{X}_i, \mathbf{X}_j] &= 0 \\ [\mathbf{P}_i, \mathbf{P}_j] &= 0 \\ [\mathbf{X}_i, \mathbf{P}_j] &= i\hbar \delta_{ij} \\ \end{align*}\]The Classical Connection

In CM momentum is mass times velocity, while in QM momentum is a differential operator. How are these two connected, and is there a way to connect CM to QM in general?

The closest we come to a classical-quantum connection is through expected values. For example, in QM the classical notion of velocity corresponds to

\[v \leftrightarrow \frac{d}{dt} \left< \mathbf{X} \right>\]To see why, start by looking at the time-derivative in terms of the Hamiltonian commutator:

\[\frac{d}{dt}\left<\mathbf{X}\right> = -\frac{i}{\hbar}\left<\left[\mathbf{X},\mathbf{H}\right]\right>\]In the absence of a potential the right side simplifies to \(\left< \mathbf{P} \right>/m\), which is the classical result for velocity. It’s interesting that in QM momentum is emphasized over velocity, and that velocity doesn’t appear explicitly like in CM.

What about when a potential is present? In CM the dynamics are

\[\frac{dp}{dt} = -\frac{dV}{dx}\]In QM the left side becomes

\[\frac{d}{dt}\left<\mathbf{P}\right> = -\frac{i}{\hbar}\left<[\mathbf{P},\mathbf{H}]\right>\]The Hamiltonian is

\[\mathbf{H} = \frac{\mathbf{P}^2}{2m} + \mathbf{V}(x)\]Which leads to

\[\frac{d}{dt}\left<\mathbf{P}\right> = -\left<\frac{dV}{dx}\right>\]So the quantum result looks like the classical result in expectation, except that the right side takes the expectation over the entire derivative, which in general is different from taking it over \(x\) and then differentiating. In other words,

\[\left<\frac{dV}{dx}\right> \neq \frac{dV}{dx} \bigg|_{x=\left<x\right>}\]If the right-side were true, we could think of a particle as classically “being” at \(\left<x\right>\) and moving according to the potential there, just like a classical particle does, but this isn’t the case. In QM, wavefunctions are spread-out in space and therefore “feel” potentials as a distribution—the entire potential function needs to be considered. If, however, the potential is approximately the same across the width of the wavefunction then the \(\neq\) can be replaced by \(=\), which is the classical limit.

Last

This ends the summary of dynamics & continuous states in quantum mechanics. The framework laid here provides a basis for modeling realistic systems such as free particles, spatially constrained particles, harmonic oscillators, and hydrogen atoms, all of which are covered in the next section. To be continued…